This page is part of the Clinical Quality Language Specification (v1.5.3: Normative - Normative) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

| Page standards status: Normative | Maturity Level: N |

This chapter introduces the high-level syntax for the Clinical Quality Language focused on measure and decision support authors. This syntax provides a human-readable, yet precise mechanism for expressing logic in both the measurement and improvement domains of clinical quality.

The syntax, or structure, of CQL is built from several basic elements that are all classified as tokens. There are four different types of tokens present in CQL: symbols, such as + and *, keywords, such as define and from, literals, such as 5 and 'active', and identifiers, such as Person and "Inpatient Encounters".

Statements of CQL are built up by combining these basic elements, separated by whitespace (spaces, tabs, and returns), to produce language elements. The most basic of these language elements is an expression, which is any statement of CQL that returns a value.

Expressions are made up of terms (literals or identifiers) combined using operators. Operators can be symbolic, such as + and -, phrases such as and and exists, or named operators called functions, such as First() and AgeInYears().

At the highest level, CQL is organized around the concept of a library, which can be thought of as a container for artifact logic. Libraries contain declarations which specify the items the library contains. The most important of these declarations is the named expression, which is the basic unit of logic definition in CQL.

In the sections that follow, the various constructs introduced above will be discussed in more detail, beginning with the kinds of declarations that can be made in a CQL library, and then moving through the various ways that clinical information is referenced and queried within CQL, followed by an overview of the operators available in CQL, and ending with a detailed walkthrough of authoring specific quality artifacts using a running example.

It is important to keep in mind throughout the discussion that follows that CQL is a query language, which means that the statements of the language are really questions, formulated in terms of a data model that describes the available data. Depending on the use case, these questions will be evaluated in different ways to produce a response. For example, for decision support, the questions will likely be evaluated in the context of a specific patient and at some specific point in a workflow. For quality measurement, the questions will likely be evaluated for each of a set of patients in an overall population. However the evaluation occurs, the discussions in this chapter refer generally to the notion of an evaluation request that represents a request by some consumer to evaluate a CQL expression. This evaluation request generally includes the context of the evaluation (i.e. the inputs to the evaluation such as the patient and any parameter values), as well as a timestamp associated with when the evaluation request occurs.

Throughout the discussion, readers may find it helpful to refer to Appendix B – CQL Reference for more detailed discussion of particular concepts.

And as a final introductory note, CQL is designed to support two levels of usage. The first level focuses on the simplest possible expression of the most common use cases encountered in quality measurement and decision support, while the second level focuses on more advanced capabilities such as multi-source queries and user-defined functions. The first level is covered in this chapter, the Author's Guide, while the second level is covered in the next chapter, the Developer's Guide.

Constructs expressed within CQL are packaged in containers called libraries. Libraries provide a convenient unit for the definition, versioning, and distribution of logic. For simplicity, libraries in CQL correspond directly with a single file.

Libraries in CQL provide the overall packaging for CQL definitions. Each library allows a set of declarations to provide information about the library as well as to define constructs that will be available within the library.

Libraries can contain any or all of the following constructs:

| Construct | Description |

|---|---|

| library | Header information for the library, including the name and version, if any. |

| using | Data model information, specifying that the library may access types from the referenced data model. |

| include | Referenced library information, specifying that the library may access constructs defined in the referenced library. |

| codesystem | Codesystem information, specifying that logic within the library may reference the specified codesystem by the given name. |

| valueset | Valueset information, specifying that logic within the library may reference the specified valueset by the given name. |

| code | Code information, specifying that logic within the library may reference the specified code by the given name. |

| concept | Concept information, specifying that logic within the library may reference the specified concept by the given name. |

| parameter | Parameter information, specifying that the library expects parameters to be supplied by the evaluating environment. |

| context | Specifies the overall context, such as Patient or Practitioner, to be used in the statements that are declared in the library. Note that a library may have multiple context declarations, and that each context declaration establishes the context for the statements that follow, until the next context declaration is encountered. However, best practice is that each library should only contain a single context declaration as the first statement in the library. |

| define | The basic unit of logic within a library, a define statement introduces a named expression that can be referenced within the library, or by other libraries. |

| function | Libraries may also contain function definitions. A function in CQL is a named expression that is allowed to take any number of arguments, each of which has a name and a declared type. These are most often used as part of shared libraries. |

Table 2‑A - Constructs that CQL libraries can contain

A syntax diagram of a library containing all of the constructs can be seen here.

The following sections discuss these constructs in more detail.

The library declaration specifies both the name of the library and an optional version for the library. The library name is used as an identifier to reference the library from other CQL libraries, as well as eCQM and CDS artifacts. A library can have at most one library declaration.

The following example illustrates the library declaration:

library CMS153_CQM version '2'

The above declaration names the library with the identifier CMS153_CQM and specifies the version '2'.

A syntax diagram of the library declaration can be seen here.

A CQL library can reference zero or more data models with using declarations. These data models define the structures that can be used within retrieve expressions in the library.

For more information on how these data models are used, see the Retrieve section.

The following example illustrates the using declaration:

using QUICK

The above declaration specifies that the QUICK model will be used as the data model within the library. The QUICK data model will be used for the examples in this section unless specified otherwise.

If necessary, a version specifier can be provided to indicate which version of the data model should be used as shown below:

using QUICK version '0.3.0'

A syntax diagram of the using declaration can be seen here.

A CQL library can reference zero or more other CQL libraries with include declarations. Components defined within these included libraries can then be referenced within the library by name.

include CMS153_Common

Components defined in the CMS153_Common library can now be referenced using the library name. For example:

define "SexuallyActive":

exists (CMS153_Common."ConditionsIndicatingSexualActivity")

or exists (CMS153_Common."LaboratoryTestsIndicatingSexualActivity")

This expression references ConditionsIndicatingSexualActivity and LaboratoryTestsIndicatingSexualActivity defined in the CMS153_Common library.

The syntax used to reference these expressions is a qualified identifier consisting of two parts. The qualifier, CMS153_Common, and the identifier, ConditionsIndicatingSexualActivity, separated by a dot (.).

For more information on libraries, refer to the Using Libraries to Share Logic section.

The include declaration may optionally specify a version, meaning that a specific version of the library must be used:

include CMS153_Common version '2'

A more in-depth discussion of library versioning is provided in the Libraries section of the Developers guide.

In addition, the include declaration may optionally specify an assigned name using the called clause:

include CMS153_Common version '2' called Common

Components defined in the CMS153_Common library, version 2, can now be referenced using the assigned name of Common. For example:

define "SexuallyActive":

exists (Common."ConditionsIndicatingSexualActivity")

or exists (Common."LaboratoryTestsIndicatingSexualActivity")

A syntax diagram of the include declaration can be seen here.

A CQL library may contain zero or more named terminology declarations, including codesystems, valuesets, codes, and concepts, using the codesystem, valueset, code, and concept declarations.

These declarations specify a local name that represents a codesystem, valueset, code, or concept and can be used anywhere within the library where the terminology is expected.

The syntax diagrams of the codesystem definition,valueset definition, code definition and concept definition.

Consider the following valueset declaration:

valueset "Female Administrative Sex": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.560.100.2'

This definition establishes the local name "Female Administrative Sex" as a reference to the external identifier for the valueset, more specifically, an Object Identifier (OID) in this particular case: 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.560.100.2'. The external identifier need not be an OID; instead, it may be a uniform resource identifier (URI), or any other identification system. CQL does not interpret the external id, it only specifies that the external identifier be a string that can be used to uniquely identify the valueset within the implementation environment.

This valueset definition can then be used within the library wherever a valueset can be used:

define "PatientIsFemale": Patient.gender in "Female Administrative Sex"

The above example defines the PatientIsFemale expression as true for patients whose gender is a code in the valueset identified by "Female Administrative Sex".

Note that the name of the valueset uses double quotes, unlike the string representation of the OID for the valueset, which uses single quotes. Single quotes are used to build arbitrary strings in CQL; double quotes are used to represent names of constructs such as valuesets and expression definitions.

Note also that the local name for a valueset is user-defined and not required to match the actual name of the valueset identified within the external valueset repository. However, when using external terminologies, authors should use the name of the terminology as defined externally to avoid introducing any potential confusion of meaning.

The following example illustrates a code system and a code declaration:

codesystem "SNOMED": 'http://snomed.info/sct'

code "Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis (procedure)":

'442487003' from "SNOMED" display 'Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis (procedure)'

This codesystem declaration in this example establishes the local name "SNOMED" as a reference to the external identifier for the codesystem, the URI "http://snomed.info/sct". The code declaration in this example establishes the local name "Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis (procedure)" as a reference to the code '442487003' from the "SNOMED" code system already defined.

For more information about terminologies as values within CQL, refer to the Clinical Values section.

A CQL library can define zero or more parameters. Each parameter is defined with the elements listed in the following table:

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | A unique identifier for the parameter within the library |

| Type | The type of the parameter – Note that the type is only required if no default value is provided. Otherwise, the type of the parameter is determined based on the default value. |

| Default Value | An optional default value for the parameter |

Table 2‑B - Elements that define a parameter

A syntax diagram of the parameter can be seen here.

The parameters defined in a library may be referenced by name in any expression within the library. When expressions in a CQL library are evaluated, the values for parameters are provided by the environment. For example, a library that defines criteria for a quality measure may define a parameter to represent the measurement period:

parameter MeasurementPeriod default Interval[@2013-01-01, @2014-01-01)

Note the syntax for the default here is called an interval selector and will be discussed in more detail in the section on Interval Values.

This parameter definition can now be referenced anywhere within the CQL library:

define "Patient16To23":

AgeInYearsAt(start of MeasurementPeriod) >= 16

and AgeInYearsAt(start of MeasurementPeriod) < 24

The above example defines the Patient16To23 expression as patients whose age at the start of the MeasurementPeriod was at least 16 and less than 24.

The default value for a parameter is optional, but if no default is provided, the parameter must include a type specifier:

parameter MeasurementPeriod Interval<DateTime>

If a parameter definition does not indicate a default value, a parameter value may be supplied by the evaluation environment, typically as part of the evaluation request. If the evaluation environment does not supply a parameter value, the parameter will be null.

In addition, because parameter defaults are part of the declaration, the expressions used to define them have the following restrictions applied:

. Parameter defaults cannot reference run-time data (i.e. they cannot contain Retrieve expressions) . Parameter defaults cannot reference expressions or functions defined in the current library . Parameter defaults cannot reference included libraries . Parameter defaults cannot perform terminology operations. For more information on terminology operations, see the Terminology Operators section. . Parameter defaults cannot reference other parameters

In other words, the value for the default of a parameter must be able to be calculated at compile-time.

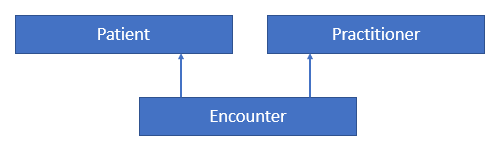

The context declaration defines the scope of data available to statements within the language. Models define the available contexts, including at least one context named Unfiltered that indicates that statements are not restricted to a particular context. Consider the following simplified information model:

Figure 2-A - Simplified patient/practitioner information model

A patient and practitioner may both have any number of encounters. From the perspective of a patient (i.e. in patient context), only encounters for that particular patient are accessible. Likewise, from the perspective of a practitioner (i.e. in practitioner context), only encounters for that particular practitioner are accessible.

The following table lists some typical contexts:

| Context | Description |

|---|---|

| Patient | The Patient context specifies that expressions should be interpreted with reference to a single patient. |

| Practitioner | The Practitioner context specifies that expressions should be interpreted with reference to a single practitioner. |

| Unfiltered | The Unfiltered context indicates that expressions are not interpreted with reference to a particular context. |

Table 2‑C - Typical contexts for CQL

A syntax diagram of the context declaration can be seen here.

Depending on different needs, models may define any context appropriate to their use case, but should identify a default context that is used when authors do not declare a specific context.

When no context is specified in the library, and the model has not declared a default context, the default context is Unfiltered.

context Patient

define "Patient16To23AndFemale":

AgeInYearsAt(start of MeasurementPeriod) >= 16

and AgeInYearsAt(start of MeasurementPeriod) < 24

and Patient.gender in "Female Administrative Sex"

Because the context has been established as Patient, the expression has access to patient-specific concepts such as the AgeInYearsAt() operator and the Patient.gender attribute. Note that the attributes available in the Patient context are defined by the data model in use.

A library may contain zero or more context statements, with each context statement establishing the context for subsequent statements in the library.

Effectively, the statement context Patient defines an expression named Patient that returns the patient data for the current patient, as well as restricts the information that will be returned from a retrieve to a single patient, as opposed to all patients.

As another example, consider a Practitioner context:

context Practitioner

define "Encounters":

["Encounter": "Inpatient Encounter"]

The above definition results in all the encounters for a particular practitioner. For more information on context, refer to the Retrieve Context discussion below.

A CQL Library can contain zero or more define statements describing named expressions that can be referenced either from other expressions within the same library or by containing quality and decision support artifacts.

The following example illustrates a simple define statement:

define "InpatientEncounters":

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

where E.length <= 120 days

and E.period ends during MeasurementPeriod

This example defines the InpatientEncounters expression as Encounter events whose code is in the "Inpatient" valueset, whose length is less than or equal to 120 days, and whose period ended (i.e. patient was discharged) during MeasurementPeriod.

Note that the use of terms like Encounter, length, and period, as well as which code attribute is used to compare with the valueset, are defined by the data model being used within the library; they are not defined by CQL.

For more information on the use of define statements, refer to the Using Define Statements section.

The retrieve expression is the central construct for accessing clinical information within CQL. The result of a retrieve is always a list of some type of clinical data, based on the type described by the retrieve and the context (such as Patient, Practitioner, or Unfiltered) in which the retrieve is evaluated.

The retrieve in CQL has two main parts: first, the type part, which identifies the type of data that is to be retrieved; and second, the filter part, which optionally provides filtering information based on specific types of filters common to most clinical data.

A syntax diagram of the retrieve expression can be seen here.

Note that the retrieve only introduces data into an expression; operations for further filtering, shaping, computation, and sorting will be discussed in later sections.

The retrieve expression is a reflection of the idea that clinical data in general can be viewed as clinical statements of some type as defined by the model. The type of the clinical statement determines the structure of the data that is returned by the retrieve, as well as the semantics of the data involved.

The type may be a general category, such as a Condition, Procedure, or Encounter, or a more specific instance such as an ImagingProcedure or a LaboratoryTest. The data model defines the available types that may be referenced by a retrieve.

In the simplest case, a retrieve specifies only the type of data to be retrieved. For example:

[Encounter]

Assuming the default context of Patient, this example retrieves all Encounter statements for a patient.

In addition to describing the type of clinical statements, the retrieve expression allows the results to be filtered using terminology, including valuesets, code systems, or by specifying a single code. The use of codes within clinical data is ubiquitous, and most clinical statements have at least one code-valued attribute. In addition, there is typically a “primary” code-valued attribute for each type of clinical statement. This primary code is used to drive the terminology filter. For example:

[Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"]

This example requests only those Conditions whose primary code attribute is a code from the valueset identified by "Acute Pharyngitis". The attribute used as the primary code attribute is defined by the data model being used.

In addition, the retrieve expression allows the filtering attribute name to be specified:

[Condition: severity in "Acute Severity"]

This requests clinical statements that assert the presence of a condition with a severity in the "Acute Severity" valueset.

Note that the terminology reference "Acute Severity" in the above examples is a valueset, but it could also be a code system, a concept, or a specific code:

codesystem "SNOMED": 'http://snomed.info/sct'

code "Acute Pharyngitis Code":

'363746003' from "SNOMED" display 'Acute pharyngitis (disorder)'

define "Get Condition from Code Declaration":

[Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis Code"]

define "Get Condition from CodeSystem Declaration":

[Condition: "SNOMED"]

The "Get Condition from Code Declaration" expression returns conditions for the patient where the code is equivalent to the "Acute Pharyngitis Code" code. The "Get Condition from CodeSystem Declaration" expression returns conditions for the patient where the code is some code in the "SNOMED" code system.

When the primary code attribute is used (i.e. no filtering attribute name is specified in the retrieve), the retrieve uses the membership operator (in) if the terminology target is a valueset or code system, and the equivalent operator (~) otherwise. For more information about using the equivalent operator with terminology, refer to the Code section. For more information about using the membership operator with terminology, refer to the Terminology Operators section.

When the code path is specified, the code comparison operation can be specified as well:

codesystem "SNOMED": 'http://snomed.info/sct'

code "Acute Pharyngitis Code":

'363746003' from "SNOMED" display 'Acute pharyngitis (disorder)'

define "Get Condition from Code Declaration":

[Condition: code ~ "Acute Pharyngitis Code"]

define "Get Condition from CodeSystem Declaration":

[Condition: code in "SNOMED"]

define "Get Condition from Exact Match To Code":

[Condition: code = "Acute Pharyngitis Code"]

Note the last example here is using the equality operator (=) to indicate the terminology match should be exact (meaning that it will consider code system version and display as well as the code and system). Equality, equivalence, and membership are the only allowed terminology comparison operators within a retrieve.

Within the Patient context, the results of any given retrieve will always be scoped to a single patient, as determined by the environment. For example, in a quality measure evaluation environment, the Patient context may be the current patient being considered. In a clinical decision support environment, the Patient context would be the patient for which guidance is being sought.

By contrast, if the Unfiltered context is used, the results of any given retrieve will not be limited to a particular context. For example:

[Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"] C where C.onsetDateTime during MeasurementPeriod

When evaluated within the Patient context, the above example returns "Acute Pharyngitis" conditions that onset during MeasurementPeriod for the current patient only. In the Unfiltered context, this example returns all "Acute Pharyngitis" conditions that onset during MeasurementPeriod, regardless of patient.

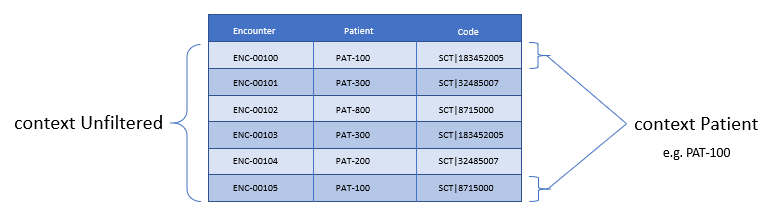

As another example, consider the set of encounters:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"]

Depending on the context the retrieve above will return:

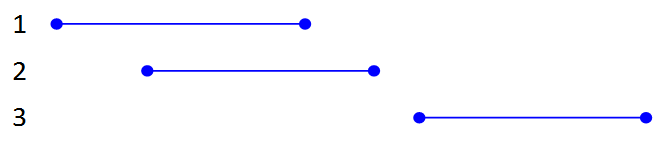

Consider the figure below:

Figure 2‑B - Unfiltered vs Patient context

Because context is associated with each declaration, it is possible for expressions defined in a particular context to reference expressions defined in the Unfiltered context and vice versa. Best practice is for each library to have expressions in only one context, and for that context declaration to be the first declaration in the library.

Note that it is not legal for an expression in one specified context to reference an expression in another specified context. This is because there must be a way to relate cross-context queries, which is only possible in the Unfiltered context, or through the use of a cross-context retrieve.

In an Unfiltered context, a reference to a specified context expression (such as Patient) results in the execution of that expression for each patient in the unfiltered context, and the implementation environment combines the results.

If the result type of an expression in a specific context is not a list, the result of accessing it from an Unfiltered context will be a list with elements of the type of the expression. For example:

context Patient

define "InInitialPopulation":

AgeInYearsAt(@2013-01-01) >= 16 and AgeInYearsAt(@2013-01-01) < 24

context Unfiltered

define "InitialPopulationCount":

Count(InInitialPopulation IP where IP is true)

In the above example, the InitialPopulationCount expression returns the number of patients for which the InInitialPopulation expression evaluated to true.

If the result type of the Patient context expression is a list, the result will be a list of the same type, but with the results of the evaluation for each patient in the unfiltered context flattened into a single list.

In a specific context (such as Patient), a reference to an Unfiltered context expression results in the evaluation of the Unfiltered context expression, and the result type is unaffected.

In some cases, measures or decision support artifacts may need to access data for a related person, such as the mother’s record from an infant’s context. For information on how to do this in CQL, refer to Related Context Retrieves.

Beyond the retrieve expression, CQL provides a query construct that allows the results of retrieves to be further filtered, shaped, and extended to enable the expression of arbitrary clinical logic that can be used in quality and decision support artifacts.

Although similar to a retrieve in that a query will typically result in a list of patient information, a query is a more general construct than a retrieve. Retrieves are by design restricted to a particular set of criteria that are commonly used when referencing clinical information, and specifically constructed to allow implementations to easily build data access layers suitable for use with CQL. For more information on the design of the retrieve construct, refer to Clinical Data Retrieval in Quality Artifacts.

The query construct has a primary source and four main clauses that each allow for different types of operations to be performed:

| Clause | Operation |

|---|---|

| Relationship (with/without) | Allows relationships between the primary source and other clinical information to be used to filter the result. |

| Where | The where clause allows conditions to be expressed that filter the result to only the information that meets the condition. |

| Return | The return clause allows the result set to be shaped as needed, removing elements, or including new calculated values. |

| Sort | The sort clause allows the result set to be ordered according to any criteria as needed. |

Table 2‑D - Four main clauses for a query construct

Each of these clauses will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

A query construct begins by introducing an alias for the primary source:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

The primary source for this query is the retrieve expression +++[+++Encounter: "Inpatient"], and the alias is E. Subsequent clauses in the query must reference elements of this source by using this alias.

Although the alias in this example is a single-letter abbreviation, E, it could also be a longer abbreviation:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] Enc

Note that alias names, as with all language constructs, may be the subject of language conventions. The Formatting Conventions section defines a very general set of formatting conventions for use with Clinical Quality Languages. Within specific domains, institutions or stakeholders may create additional conventions and style guides appropriate to their domains.

The where clause allows the results of the query to be filtered by a condition that is evaluated for each element of the query being filtered. If the condition evaluates to true for the element being tested, that element is included in the result. Otherwise, the element is excluded from the resulting list.

A syntax diagram of a where clause can be seen here.

For example:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

where duration in days of E.period >= 120

The alias E is used to access the period attribute of each encounter in the primary source. The filter condition tests whether the duration of that range is at least 120 days.

The condition of a where clause is allowed to contain any arbitrary combination of operations of CQL, so long as the overall result of the condition is boolean-valued. For example, the following where clause includes multiple conditions on different attributes of the source:

[CommunicationRequest] C

where C.mode = 'ordered'

and C.sender.role = 'nurse'

and C.recipient.role = 'doctor'

and C.indication in "Fever"

Note that because CQL uses three-valued logic, the result of evaluating any given boolean-valued condition may be unknown (null). For example, if the list of inpatient encounters from the first example contains some elements whose period attribute is null, the result of the condition for that element will not be false, but null, indicating that it is not known whether or not the duration of the encounter was at least 120 days. For the purposes of evaluating a filter, only elements where the condition evaluates to true are included in the result, effectively ignoring the entries for which the logical expression evaluates to null. For more discussion on three-valued logic, see the section on Missing Information in the Author's Guide, as well as the section on Nullological Operators in the Developer's guide.

The return clause of a CQL query allows the results of the query to be shaped. In most cases, the results of a query will be of the same type as the primary source of the query. However, some scenarios require only specific elements be extracted, or computations on the data involved in each element be performed. The return clause enables this type of query.

A syntax diagram of a return clause can be seen here.

For example:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

return Tuple { id: E.identifier, lengthOfStay: duration in days of E.period }

This example returns a list of tuples (structured values), one for each inpatient encounter performed, where each tuple consists of the id of the encounter as well as a lengthOfStay element, whose value is calculated by taking the duration of the period for the encounter. Tuples are discussed in detail in later sections. For more information on Tuples, see Structured Values (Tuples).

By default, a query returns a list of distinct results, suppressing duplicates. To include duplicates, use the all keyword in the return clause. For example, the following will return a list of the lengths of stay for each Encounter:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

return E.lengthOfStay

If two encounters have the same value for lengthOfStay, that value will only appear once in the result unless the all keyword is used:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

return all E.lengthOfStay

CQL queries can sort results in any order using the sort by clause.

A syntax diagram of a sort clause can be seen here.

For example:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E sort by start of period

This example returns inpatient encounters, sorted by the start of the encounter period.

Results can be sorted ascending or descending using the asc (ascending) or desc (descending) keywords:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E sort by start of period desc

If no ascending or descending specifier is provided, the order is ascending.

Calculated values can also be used to determine the sort:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

return Tuple { id: E.identifier, lengthOfStay: duration in days of E.period }

sort by lengthOfStay

Note that the properties that can be specified within the sort clause are determined by the result type of the query. In the above example, [id]#lengthOfStay# can be referenced because it is introduced in the return clause. Because the sort applies after the query results have been determined, alias references are neither required nor allowed in the sort.

If no sort clause is provided, the order of the result is unprescribed and is implementation specific.

The sort clause may include multiple attributes, each with their own sort order:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E sort by start of period desc, identifier asc

Sorting is performed in the order in which the attributes are defined in the sort clause, so this example sorts by period descending, then by identifier ascending.

When the sort elements do not provide a unique ordering (i.e. there is a possibility of duplicate sort values in the result), the order of duplicates is unspecified.

A query may only contain a single sort clause, and it must always appear last in the query.

When the data being sorted includes nulls, they are considered lower than any non-null value, meaning they will appear at the beginning of the list when the data is sorted ascending, and at the end of the list when the data is sorted descending.

Within the expressions of a sort clause, the iteration accessor $this may be used to access the current iteration element, and $index may be used to access the 0-based index of the current iteration.

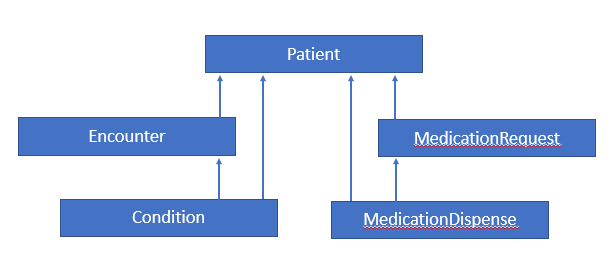

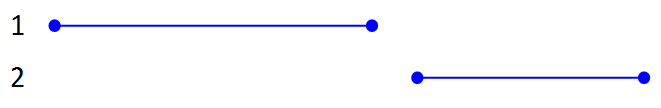

In addition to filtering by conditions, some scenarios need to be able to filter based on relationships to other sources. The CQL with and without clauses provide this capability. For the examples in this section, consider the following simple information model:

Figure 2‑C - Simple patient information model

[Encounter: "Ambulatory/ED Visit"] E

with [Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"] P

such that P.onsetDateTime during E.period

and P.abatementDate after end of E.period

This query returns "Ambulatory/ED Visit" encounters performed where the patient also has a condition of "Acute Pharyngitis" that overlaps after the period of the encounter.

The without clause returns only those elements from the primary source that do not have a specific relationship to another source. For example:

[Encounter: "Ambulatory/ED Visit"] E

without [Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"] P

such that P.onsetDateTime during E.period

and P.abatementDate after end of E.period

This query is the same as the previous example, except that only encounters that do not have overlapping conditions of "Acute Pharyngitis" are returned. In other words, if the such that condition evaluates to true (if the Encounter has an overlapping Condition of Acute Pharyngitis in this case), then that Encounter is not included in the result.

A syntax diagram of a with clause and without clause.

A given query may include any number of with and without clauses in any order, but they must all come before any where, return, or sort clauses.

The such that conditions in the examples above used Timing Relationships (e.g. during, after end of), but any expression may be used, so long as the overall result is boolean-valued. For example:

[MedicationDispense: "Warfarin"] D

with [MedicationPrescription: "Warfarin"] P

such that P.status = 'active'

and P.identifier = D.authorizingPrescription.identifier

This example retrieves all dispense records for active prescriptions of Warfarin.

When multiple with or without clauses appear in a single query, the result will only include elements that meet the such that conditions for all the relationship clauses. For example:

MeasurementPeriodEncounters E

with Pharyngitis P

such that Interval[P.onsetDateTime, P.abatementDateTime] includes E.period

or P.onsetDateTime.value in E.period

with Antibiotics A such that A.dateWritten 3 days or less after start of E.period

This example retrieves all the elements returned by the expression MeasurementPeriodEncounters that have both a related Pharyngitis and Antibiotics result.

The clauses described in the previous section must appear in the correct order in order to specify a valid CQL query. The general order of clauses is:

<primary-source> <alias>

<with-or-without-clauses>

<where-clause>

<return-clause>

<sort-clause>

A query must contain an aliased primary source, but this is the only required clause.

A query may contain zero or more with or without clauses, but they must all appear before any where, return, or sort clauses.

A query may contain at most one where clause, and it must appear after any with or without clauses, and before any return or sort clauses.

A query may contain at most one return clause, and it must appear after any with or without or where clauses, and before any sort clause.

A query may contain at most one sort clause, and it must be the last clause in the query.

For example:

[Encounter: "Inpatient"] E

with [Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"] P

such that P.onsetDateTime during E.period

and P.abatementDate after end of E.period

where duration in days of E.period >= 120

return Tuple { id: E.id, lengthOfStay: duration in days of E.period }

sort by lengthOfStay desc

This query returns all "Inpatient" encounter events that have an overlapping condition of "Acute Pharyngitis" and a duration of at least 120 days. For each such event, the result will include the id of the event and the duration in days, and the results will be ordered by that duration descending.

As another example, consider a query with multiple without clauses:

SingleLiveBirthEncounter E

without [Condition: "Galactosemia"] G

such that G.onsetDatetime during E.period

without [Procedure: "Parenteral Nutrition"] P

such that P.performed starts during E.period

where not exists ( E.diagnosis ED

where ED.code in "Galactosemia"

)

Even though this example has multiple without clauses, there is still only a single where clause for the query.

Note that the query construct in CQL supports other clauses that are not discussed here. For more information on these, refer to Introducing Scoped Definitions In Queries and Multi-Source Queries.

CQL supports several categories of values:

The result of evaluating any expression in CQL is a value of some type. For example, the expression 5 results in the value 5 of type Integer. CQL is a strongly-typed language, meaning that every value is of some type, and that every operation expects arguments of a particular type.

As a result, any given expression of CQL can be verified as meaningful or be determined meaningless, at least in terms of the operations performed. For example, consider the following expression:

6 + 6

The expression involves the addition of values of type Integer, and so is a meaningful expression of CQL. By contrast:

6 + 'active'

This expression involves the addition of a value of type Integer, 6, to a value of type String, 'active'. This expression is meaningless since CQL does not define addition for values of type Integer and String.

However, there are cases where an expression is meaningful, even if the types do not match exactly. For example, consider the following addition:

6 + 6.0

This expression involves the addition of a value of type Integer, and a value of type Decimal. This is meaningful, but in order to infer the correct result type, the Integer value will be implicitly converted to a value of type Decimal, and the Decimal addition operator will be used, resulting in a value of type Decimal.

To ensure there can never be a loss of information, this implicit conversion will only happen from Integer to Decimal, never from Decimal to Integer.

In the sections that follow, the various categories of values that can be represented in CQL will be considered in more detail.

CQL supports several types of simple values:

| Value | Examples |

|---|---|

| Boolean | true, false, null |

| Integer | 16, -28 |

| Decimal | 100.015 |

| String | 'pending', 'active', 'complete' |

| Date | @2014-01-25 |

| DateTime | @2014-01-25T14:30:14.559 @2014-01T |

| Time | @T12:00 @T14:30:14.559 |

Table 2‑E - Types of simple values that CQL supports

The Boolean type in CQL supports the logical values true, false, and null (meaning unknown). These values are most often encountered as the result of Comparison Operators, and can be combined with other boolean-valued expressions using Logical Operators. Note that CQL supports three-valued logic, see the section on Missing Information in the Author's Guide, as well as the section on Nullological Operators in the Developer's guide for more information.

The Integer type in CQL supports the representation of whole numbers, positive and negative. CQL supports a full set of Arithmetic Operators for performing computations involving whole numbers.

In addition, any operation involving Decimal values can be used with values of type Integer because Integer values can always be implicitly converted to Decimal values.

The Decimal type in CQL supports the representation of real numbers, positive and negative. As with Integer values, CQL supports a full set of Arithmetic Operators for performing computations involving real numbers.

String values within CQL are represented using single-quotes:

'active'

Note that if the value you are attempting to represent contains a single-quote, use a backslash to include it within the string in CQL:

'patient\'s condition is normal'

Comparison of String values in CQL is case-sensitive, meaning that the strings 'patient' and 'Patient' are not equal:

'Patient' = 'Patient'

'Patient' != 'patient'

'Patient' ~ 'patient'

For case- and locale-insensitive comparison, locale-insensitive meaning that an operator will behave identically for all users, regardless of their system locale settings, use the equivalent (~) operator. Note that string equivalence will also "normalize whitespace", meaning that all whitespace characters are treated as equivalent.

CQL supports the representation of Date, DateTime, and Time values.

A syntax diagram of a Date, DateTime and Time format can be seen here.

DateTime values are used to represent an instant along the timeline, known to at least the year precision, and potentially to the millisecond precision. DateTime values are specified using an at-symbol (@) followed by an ISO-8601 textual representation of the DateTime value:

@2014-01-25T14:30

@2014-01-25T14:30:14.559

Date values are used to represent only dates on a calendar, irrespective of the time of day. Date values are specified using an at-symbol (@) followed by an ISO-8601 textual representation of the Date value:

@2014-01-25

Note that the Date value literal format is identical to the date value portion of the DateTime literal format.

Time values are used to represent a time of day, independent of the date. Time value must be known to at least the hour precision, and potentially to the millisecond precision. Time values are specified using an at-symbol with a capital T (@T) followed by an ISO-8601 textual representation of the Time value:

@T12:00

@T14:30:14.559

Note that the Time value literal format is identical to the time value portion of the DateTime literal format.

Only DateTime values may specify a timezone offset, either as UTC (Z), or as a timezone offset. If no timezone offset is specified, the timezone offset of the evaluation request timestamp is used.

For both DateTime and Time values, although the milliseconds are specified with a separate component, seconds and milliseconds are combined and represented as a Decimal for the purposes of comparison, duration, and difference calculation. In other words, when performing comparisons or calculations for precisions of seconds and above, if milliseconds are not specified, the calculation should be performed as though milliseconds had been specified as 0.

For more information on the use of date and time values within CQL, refer to the Date and Time Operators section.

Specifically, because Date, DateTime, and Time values may be specified to varying levels of precisions, operations such as comparison and duration calculation may result in null, rather than the true or false that would result from the same operation involving fully specified values. For a discussion of the effect of imprecision on date and time operations, refer to the Comparing Dates and Times section.

In addition to simple values, CQL supports some types of values that are specific to the clinical quality domain. For example, CQL supports codes, concepts, quantities, ratios, and valuesets.

A quantity is a number with an associated unit. For example:

6 'gm/cm3'

80 'mm[Hg]'

3 months

The number portion of a quantity can be an Integer or Decimal, and the unit portion is a (single-quoted) String representing a valid Unified Code for Units of Measure (UCUM) unit or calendar duration keyword, singular or plural. To avoid the possibility of ambiguity, UCUM codes shall be specified using the case-sensitive (c/s) form.

For time-valued quantities, in addition to the definite duration UCUM units, CQL defines calendar duration keywords for calendar duration units:

| Calendar Duration | Unit Representation | Relationship to Definite Duration UCUM Unit |

|---|---|---|

year/years |

'year' |

~ 1 'a' |

month/months |

'month' |

~ 1 'mo' |

week/weeks |

'week' |

= 1 'wk' |

day/days |

'day' |

= 1 'd' |

hour/hours |

'hour' |

= 1 'h' |

minute/minutes |

'minute' |

= 1 'min' |

second/seconds |

'second' |

= 1 's' |

millisecond/milliseconds |

'millisecond' |

= 1 'ms' |

Durations above days (and weeks) are calendar durations that are not comparable with definite quantity UCUM duration units.

For example, the following quantities are calendar duration quantities:

1 year

4 days

Whereas the following quantities are definite duration quantities:

1 'a'

4 'd'

The table above defines the equality/equivalence relationship between calendar and definite duration quantities. For example, 1 year is not equal (=) to 1 'a' (defined in UCUM as 365.25 'd'), but it is equivalent (~) to 1 'a'.

For all but years and months, calendar durations are both equal and equivalent to the corresponding UCUM definite-time duration unit. Note that due to the possibility of leap seconds, this is not totally accurate, however, for practical reasons, implementations typically ignore leap seconds when performing date/time arithmetic.

For a discussion of the operations available for quantities, see the Quantity Operators section.

A ratio is a relationship between two quantities, expressed in CQL using standard mathematical notation:

1:128

5 'mg' : 10 'mL'

For a discussion of the operations available for ratios, see the Ratio Operators section.

The use of codes to specify meaning within clinical data is ubiquitous. CQL therefore supports a top-level construct for dealing with codes using a structure called Code that is consistent with the way terminologies are typically represented.

The Code type has the following elements:

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| code | String | The actual code within the code system. |

| display | String | A description of the code. |

| system | String | The identifier of the code system. |

| version | String | The version of the code system. |

Table 2‑F - Elements that make up a code type

A syntax diagram of a Code declaration can be seen here.

The following examples illustrate the code declaration:

codesystem "LOINC": 'http://loinc.org'

code "Blood pressure": '55284-4' from "LOINC" display 'Blood pressure'

code "Systolic blood pressure": '8480-6' from "LOINC" display 'Systolic blood pressure'

code "Diastolic blood pressure": '8462-4' from "LOINC" display 'Diastolic blood pressure'

The above declarations can be referenced directly or within a retrieve expression.

A syntax diagram of a Code referencing an existing code can be seen here.

In addition, CQL provides a Code literal that can be used to reference an existing code from a specific code system.

For example

Code '66071002' from "SNOMED-CT" display 'Type B viral hepatitis'

The example specifies the code '66071002' from a previously defined "SNOMED-CT:2014" codesystem, which specifies both the system and version of the resulting code. Note that the display clause is optional. Note that code literals are allowed in CQL for completeness. In general, authors should use code declarations rather than code literals when using codes directly.

This use of code declarations to reference a single code in a CQL expression is referred to as a direct reference code:

code "Discharge to home for hospice care (procedure)": '428361000124107' from "SNOMEDCT"

define "Encounters Discharged to Hospice":

"Encounters" E where E.dischargeDisposition ~ "Discharge to home for hospice care (procedure)"

Note the use of the equivalent operator (~) rather than equality (=). For codes, equivalence tests only that the code system and code are the same, but does not check the code system version.

Although CQL supports both version-specific and version-independent specification of and comparison to direct reference codes, artifact authors should use version-independent direct reference codes and comparisons unless there is a specific reason not to (such as the code is retired in the current version). Even when using version-specific direct reference codes, authors should use equivalence for the comparison (again, unless there is a specific reason to use version-specific comparison with equality).

When using direct reference codes, authors should use the name of the code as defined externally to avoid introducing any potential confusion of meaning.

Using direct-reference codes can be more difficult for implementations to map to local settings, because modification of the codes for local usage may require modification of the CQL, as opposed to the use of a value set which many systems already have support for mapping to local codes.

Within clinical information, multiple terminologies can often be used to code for the same concept. As such, CQL defines a top-level construct called Concept that allows for multiple codes to be specified.

The Concept type has the following elements:

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| codes | List<Code> | The list of semantically equivalent codes representing the concept. |

| display | String | A description of the concept. |

Table 2‑G - Elements that make up a Concept type

Note that the semantics of Concept are such that the codes within a given concept should be semantically about the same concept (e.g. the same concept represented in different code systems, or the same concept from the same code system represented at different levels of detail), but CQL itself will make no attempt to ensure that is the case. Concepts should never be used as a surrogate for proper valueset definition.

The following example illustrates the concept declaration:

codesystem "SNOMED-CT": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.6.96'

codesystem "ICD-10-CM": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.6.90'

code "Hepatitis Type B (SNOMED)": '66071002' from "SNOMED-CT" display 'Viral hepatitis type B (disorder)'

code "Hepatitis Type B (ICD-10)": 'B18.1' from "ICD-10-CM" display 'Chronic viral hepatitis B without delta-agent'

concept "Type B Hepatitis": { "Hepatitis Type B (SNOMED)", "Hepatitis Type B (ICD-10)" } display 'Type B Hepatitis'

The above declaration can be referenced directly or within a retrieve expression.

A syntax diagram of a Concept declaration can be seen here.

As with codes, local names for concept declarations should be consistent with external declarations to avoid introducing any confusion of meaning.

The following example illustrates the use of a Concept literal:

Concept {

Code '66071002' from "SNOMED-CT",

Code 'B18.1' from "ICD-10-CM"

} display 'Type B viral hepatitis'

This example constructs a Concept with display 'Type B viral hepatitis' and code of '66071002'.

A syntax diagram of a Concept literal can be seen here.

As a value, a valueset is simply a list of Code values. However, CQL allows valuesets to be used without reference to the codes involved by declaring valuesets as a special type of value within the language.

A syntax diagram of a valueset declaration can be seen here.

The following example illustrates some typical valueset declarations:

valueset "Acute Pharyngitis": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.464.1003.102.12.1011'

valueset "Acute Tonsillitis": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.464.1003.102.12.1012'

valueset "Ambulatory/ED Visit": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.464.1003.101.12.1061'

Each valueset declaration defines a local identifier that can be used to reference the valueset within the library, as well as the global identifier for the valueset, typically an object identifier (OID) or uniform resource identifier (URI).

These valueset identifiers can then be used throughout the library. For example:

define "Pharyngitis": [Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"]

This example defines Pharyngitis as any Condition where the code is in the "Acute Pharyngitis" valueset.

Whenever a valueset reference is actually evaluated, the resulting expansion set, or list of codes, depends on the binding specified by the valueset declaration. By default, all valueset bindings are dynamic, meaning that the expansion set should be constructed using the most current published version of the valueset.

However, CQL also allows for static bindings which allow two components to be set:

If the binding specifies a valueset version, then the expansion set must be derived from that specific version. This does not restrict the code system versions available for use, therefore more than one expansion set is possible.

If any code systems are specified, they indicate which version of the particular code system should be used when constructing the expansion set. As with valuesets, if no code system version is specified, the expansion set should be constructed using the most current published version of the codesystem. Note that if the external valueset definition explicitly states that a particular version of a code system should be used, then it is an error if the code system version specified in the CQL static binding does not match the code system version specified in the external valueset definition. To create a reliable static binding where only one value set expansion set is possible, both the value set version and the code system versions should be specified.

The following example illustrates the use of static binding based only on the version of the valueset:

valueset "Diabetes": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.464.1003.103.12.1001' version '20140501'

The next example illustrates a static binding based on both the version of the valueset, as well as the versions of the code systems within the valueset:

codesystem "SNOMED-CT:2013-09": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.6.96' version '2031-09'

codesystem "ICD-9-CM:2014": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.6.103' version '2014'

codesystem "ICD-10-CM:2014": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.6.90' version '2014'

valueset "Diabetes": 'urn:oid:2.16.840.1.113883.3.464.1003.103.12.1001' version '20140501'

codesystems { "SNOMED-CT:2013-09", "ICD-9-CM:2014", "ICD-10-CM:2014" }

When using value set declarations, authors should use the name of the value set as defined externally to avoid introducing any potential confusion of meaning. One exception to this is when different value sets are defined with the same name in an external repository, in which case some additional aspect is required to ensure uniqueness of the names within the CQL library. See the Terminology Operators section for more information on the use of valuesets within CQL.

In addition to their use as part of valueset definitions, codesystem definitions can be referenced directly within an expression, just like valueset definitions. See the Valuesets section for an example of a codesystem declaration.

For example:

codesystem "LOINC": 'http://loinc.org'

define "LOINC Observations": [Observation: "LOINC"]

The above example retrieves all observations coded using LOINC codes.

See the Terminology Operators section for more information on the use of codesystems within CQL.

Structured values, or tuples, are values that contain named elements, each having a value of some type. Clinical information such as a Medication, a Condition, or an Encounter is represented using tuples.

For example, the following expression retrieves the first Condition with a code in the "Acute Pharyngitis" valueset for a patient:

define "FirstPharyngitis":

First([Condition: "Acute Pharyngitis"] C sort by onsetDateTime desc)

The values of the elements of a tuple can be accessed using a dot qualifier (.) followed by the name of the element:

define "PharyngitisOnSetDateTime": FirstPharyngitis.onsetDateTime

Tuples can also be constructed directly using a tuple selector.

A syntax diagram of a tuple selector can be seen here.

For example:

define "Info": Tuple { Name: 'Patrick', DOB: @2014-01-01 }

If the tuple is of a specific type, the name of the type can be used instead of the Tuple keyword:

define "PatientExpression": Patient { Name: 'Patrick', DOB: @2014-01-01 }

If the name of the type is specified, the tuple selector may only contain elements that are defined on the type, and the expressions for each element must evaluate to a value of the defined type for the element. Any elements defined in the class but not present in the selector will be null.

Note that tuples can contain other tuples, as well as lists:

define "Info":

Tuple {

Name: 'Patrick',

DOB: @2014-01-01,

Address: Tuple { Line1: '41 Spinning Ave', City: 'Dayton', State: 'OH' },

Phones: { Tuple { Number: '202-413-1234', Use: 'Home' } }

}

Accordingly, element access can nest as deeply as necessary:

Info.Address.City

This accesses the City element of the Address element of Info. Lists can be traversed within element accessors using the list indexer ([]):

Info.Phones[0].Number

This accesses the Number element of the first element of the Phones list within Info.

In addition, to simplify path traversal for models that make extensive use of list-valued attributes, the indexer can be omitted:

Info.Phones.Number

The result of this invocation is a list containing the Number elements of all the Phones within Info.

Because clinical information is often incomplete, CQL provides a special construct, null, to represent an unknown or missing value or result. For example, the admission date of an encounter may not be known. In that case, the result of accessing the admissionDate element of the Encounter tuple is null.

In order to provide consistent behavior in the presence of missing information, CQL defines null behavior for all operations. For example, consider the following expression:

define "PharyngitisOnSetDateTime": FirstPharyngitis.onsetDateTime

If the onsetDateTime is not present, the result of this expression is null. Furthermore, nulls will in general propagate, meaning that if the result of FirstPharyngitis is null, the result of accessing the onsetDateTime element is also null.

For more information on missing information, see the Nullological Operators section.

CQL supports the representation of lists of any type of value (including other lists). Although some operations may result in lists containing mixed types, in normal use cases, lists contain items that are all of the same type.

Lists can be constructed directly, as in:

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }

But more commonly, lists of tuples are the result of retrieve expressions. For example:

[Condition: code in "Acute Pharyngitis"]

This expression results in a list of tuples, where each tuple’s elements are determined by the data model in use.

Lists in CQL use zero-based indexes, meaning that the first element in a list has index 0. For example, given the list of integers:

{ 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 }

The first element is 6 and has index 0, the second element is 7 and has index 1, and so on.

Note that in general, clinical data may be expected to contain various types of collections such as sets, bags, lists, and arrays. For simplicity, CQL deals with all collections using the same collection type, the list, and provides operations to enable dealing with different collection types. For example, a set is a list where each element is unique, and any given list can be converted to a set using the distinct operator.

For a description of the distinct operator, as well as other operations that can be performed with lists, refer to the List Operators section.

CQL supports the representation of intervals, or ranges, of values of various types. In particular, intervals of date and time values, and ranges of integers and reals.

Intervals in CQL are represented by specifying the low and high points of the Interval and whether the boundary is inclusive (meaning the boundary point is part of the interval) or exclusive (meaning the boundary point is excluded from the interval). Following standard mathematics notation, inclusive (closed) boundaries are indicated with square brackets, and exclusive (open) boundaries are indicated with parentheses.

A syntax diagram of an Interval construct can be seen here.

For example:

Interval[3, 5)

This expression results in an Interval that contains the integers 3 and 4, but not 5.

Interval[3.0, 5.0)

This expression results in an Interval that contains all the real numbers >= 3.0 and < 5.0.

Intervals can be constructed based on any type that supports unique and ordered comparison. For example:

Interval[@2014-01-01T00:00:00.0, @2015-01-01T00:00:00.0)

This expression results in an Interval that begins at midnight on January 1, 2014, ends just before midnight on December 31, 2014 and is equivalent to the following interval:

Interval[@2014-01-01T00:00:00.0, @2014-12-31T23:59:59.999]

Furthermore, take the following example:

Interval[@2014-01-01, @2015-01-01)

This expression results in an Interval that begins on January 1, 2014 at an undefined time, ends at an undefined time on December 31, 2014 and is equivalent to the following interval:

Interval[@2014-01-01, @2014-12-31]

Note that the ending boundary must be greater than or equal to the starting boundary to construct a valid interval. Attempting to specify an invalid Interval will result in a run-time error. For example:

Interval[1, -1] // Invalid interval, this will result in an error

It is valid to construct an Interval with the same start and end boundary, so long as the boundaries are inclusive:

Interval[1, 1] // Unit interval containing only the point 1

Interval[1, 1) // Invalid interval, conflicting to say it both includes and excludes 1

Such an Interval contains only a single point and can be called a unit interval. For unit intervals, the point from operator can be used to extract the single point from the interval. Attempting to use point from on a non-unit-interval will result in a run-time error.

point from Interval[1, 1] // Results in 1

point from Interval[1, 5] // Invalid extractor, this will result in an error

In addition to retrieving clinical information about a patient or set of patients, the expression of clinical knowledge artifacts often involves the use of various operations such as comparison, logical operations such as and and or, computation, and so on. To ensure that the language can effectively express a broad range of knowledge artifacts, CQL includes a comprehensive set of operations. In general, these operations are all expressions in that they can be evaluated to return a value of some type, and the type of that return value can be determined by examining the types of values and operations involved in the expression.

This means that for each operation, CQL defines the number and type of each input (argument) to the operation and the type of the result, given the types of each argument.

The following sections define the operations that can be used within CQL, divided into semantically related categories.

For all the comparison operators, the result type of the operation is Boolean, meaning they may result in true, false, or null (meaning unknown). In general, if either or both of the values being compared is null, the result of the comparison is null.

The most basic operation in CQL involves comparison of two values. This is accomplished with the built-in comparison operators:

| Operator | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| = | Equality | Returns true if the arguments are the same value. Returns false if arguments are not the same value. Returns null if either or both arguments are null |

| != | Inequality | Returns true if the arguments are not the same value. Returns false if the arguments are the same value. Returns null if either or both arguments are null |

| > | Greater than | Returns true if the left argument is greater than the right argument. Returns false if the left argument is less than the right argument, or if the arguments are the same value. Returns null if either or both arguments are null |

| < | Less than | Returns true if the left argument is less than the right argument. Returns false if the left argument is greater than the right argument, or if the arguments are the same value. Returns null if either or both arguments are null |

| >= | Greater than or equal | Returns true if the left argument is greater than or equal to the right argument. Returns false if the left argument is less than the right argument. Returns null if either or both arguments are null |

| <= | Less than or equal | Returns true if the left argument is less than or equal to the right argument. Returns false if the left argument is greater than the right argument. Returns null if either or both arguments are null |

| between | Returns true if the first argument is greater than or equal to the second argument, and less than or equal to the third argument. Returns false if the first argument is less than the second argument or greater than the third argument. Returns null if any or all arguments are null. | |

| ~ | Equivalent | Returns true if the arguments are equivalent in value, or are both null; otherwise false |

| !~ | Inequivalent | Returns true if the arguments are not equivalent and false otherwise. |

Table 2‑H - The built-in comparison operators that CQL provides

In general, the equality and inequality operators can be used on any type of value within CQL, but both arguments must be the same type. For example, the following equality comparison is legal, and returns true:

5 = 5

However, the following equality comparison is invalid because numbers and strings cannot be meaningfully compared:

5 = 'completed'

Attempting to compare numbers and strings as in this example will result in an error message indicating that there is no equality (=) operator available to compare numbers and strings.

For Decimal values, equality is defined to ignore trailing zeroes.

For Date and Time values, equality is defined to account for the possibility that the Date and Time values involved are specified to varying levels of precision. For a complete discussion of this behavior, refer to Comparing Dates and Times.

For structured values, equality returns true if the values being compared are the same type (meaning they have the same types of elements) and the values for all elements that have values are the same value. For example, the following comparison returns true:

Tuple { id: 'ABC-001', name: 'John Smith' } = Tuple { id: 'ABC-001', name: 'John Smith' }

As another example, if one tuple has a value for an element that is not present in the other tuple, the result is null:

Tuple { x: 1, y: 1 } = Tuple { x: 1, y: null }

As well, tuple equality is defined as a conjunction of equality comparisons of the elements, allowing for known unequal values to be determined. For example, the following comparison returns false because the y elements are known unequal:

Tuple { x: 1, y: 1 } = Tuple { x: null, y: 2 }

For lists, equality returns true if the lists contain the same elements in the same order. For example, the following lists are equal:

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 } = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }

And the following lists are not equal:

{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 } != { 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 }

Note that in the above example, if the second list was sorted ascending prior to the comparison, the result would be true.

For intervals, equality returns true if the intervals use the same point type and cover the same range. For example:

Interval[1,5] = Interval[1,6)

This returns true because the intervals cover the same set of points, 1 through 5.

The relative comparison operators (>, >=, <, <=) can be used on types of values that have a natural ordering such as numbers, strings, and dates.

The between operator is shorthand for comparison of an expression against an upper and lower bound. For example:

4 between 2 and 8

This expression is equivalent to:

4 >= 2 and 4 <= 8

For all the comparison operators, the result type of the operation is Boolean. Note that because CQL uses three-valued logic, if either or both of the arguments is null, the result of the comparison is null (meaning unknown). This is true for all the comparison operators except equivalent (~) and not equivalent (!~). The equivalent operator is generally the same as equality, except that it returns true if both of the arguments are null, and false if one argument is null and the other is not:

define "NullEqualityTest": 1 = null

define "NullEquivalenceTest": 1 ~ null

The expression NullEqualityTest results in null, whereas the expression NullEquivalenceTest results in false.

In addition, equivalence is defined more loosely than equality for some types:

For more detail, see the definitions of Equal and Equivalent in the CQL reference.

Combining the results of comparisons and other boolean-valued expressions is essential and is performed in CQL using the following logical operations:

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

| and | Logical conjunction |

| or | Logical disjunction |

| xor | Exclusive logical disjunction |

| not | Logical negation |

Table 2‑I - Logical operations that CQL provides

The following examples illustrate some common uses of logical operators:

AgeInYears() >= 18 and AgeInYears() < 24

INRResult > 5 or DischargedOnOverlapTherapy

Note that all these operators are defined using three-valued logic, which is defined specifically to ensure that certain well-established relationships that hold in standard Boolean (two-valued) logic also hold. The complete semantics for each operator are described in the Logical Operators section of Appendix B – CQL Reference.

To ensure that CQL expressions can be freely rewritten by underlying implementations, there is no expectation that an implementation respect short-circuit evaluation, short circuit evaluation meaning that an expression stops being evaluated once the outcome is determined. With regard to performance, implementations may use short-circuit evaluation to reduce computation, but authors should not rely on such behavior, and implementations must not change semantics with short-circuit evaluation. If a condition is needed to ensure correct evaluation of a subsequent expression, the if or case expressions should be used to guarantee that the condition determines whether evaluation of an expression will occur at run-time.

The expression of clinical logic often involves numeric computation, and CQL provides a complete set of arithmetic operations for expressing computational logic. In general, these operators have the standard semantics for arithmetic operators, with the general caveat that unless otherwise stated in the documentation for a specific operation, if any argument to an operation is null, the result is null. In addition, calculations that cause arithmetic overflow or underflow, or otherwise cannot be performed (such as division by 0) will result in null, rather than a run-time error.

The following table lists the arithmetic operations available in CQL:

| Operator | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| + | addition | Performs numeric addition of its arguments |

| - | subtraction | Performs numeric subtraction of its arguments |

| * | multiply | Performs numeric multiplication of its arguments |

| / | divide | Performs numeric division of its arguments |

| div | truncated divide | Performs integer division of its arguments |

| mod | modulo | Computes the remainder of the integer division of its arguments |

| Ceiling | Returns the first integer greater than or equal to its argument | |

| Floor | Returns the first integer less than or equal to its argument | |

| Truncate | Returns the integer component of its argument | |

| Abs | Returns the absolute value of its argument | |

| - | negate | Returns the negative value of its argument |

| Round | Returns the nearest numeric value to its argument, optionally specified to a number of decimal places for rounding | |

| Ln | natural logarithm | Computes the natural logarithm of its argument |

| Log | logarithm | Computes the logarithm of its first argument, using the second argument as the base |

| Exp | exponent | Raises e to the power given by its argument |

| ^ | exponentiation | Raises the first argument to the power given by the second argument |

Table 2‑J - Arithmetic operations that CQL provides

Operations on date and time data are an essential component of expressing clinical knowledge, and CQL provides a complete set of date and time operators. These operators broadly fall into five categories:

In addition to the literals described in the Date, DateTime, and Time section, the Date, DateTime, and Time operators allow for the construction of specific Date and Time values based on the values for their components. For example:

Date(2014, 7, 5)

DateTime(2014, 7, 5, 4, 0, 0, 0, -7)

The first example constructs the Date July 5, 2014. The second example constructs a DateTime of July 5, 2014, 04:00:00.0 UTC-07:00 (Mountain Standard Time).

The DateTime operator takes the following arguments:

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Year | Integer | The year component of the DateTime |

| Month | Integer | The month component of the DateTime |

| Day | Integer | The day component of the DateTime |

| Hour | Integer | The hour component of the DateTime |

| Minute | Integer | The minute component of the DateTime |

| Second | Integer | The second component of the DateTime |

| Millisecond | Integer | The millisecond component of the DateTime |

| Timezone Offset | Decimal | The timezone offset component of the DateTime (in hours) |

Table 2‑K - The arguments that the DateTime operator takes

The Date operator takes only the first three arguments: Year, Month, and Day.

At least one component other than timezone offset must be provided, and for any particular component that is provided, all the components of broader precision must be provided. For example:

Date(2014)

Date(2014, 7)

Date(2014, 7, 11)

Date(null, null, 11) // invalid

The first three expressions above are valid, constructing dates with a specified precision of years, months, and days, respectively. However, the fourth expression is invalid, because it attempts to create a date with a day but no year or month component.

The only component that is ever defaulted is the timezone offset component. If no timezone offset component is supplied, the timezone offset component is defaulted to the timezone offset of the timestamp associated with the evaluation request.

The Time operator takes the following arguments: